By Associate Professor of Biomedical Sciences at Bond's Faculty of Health Sciences & Medicine, Dr Lotti Tajouri.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

Viruses are the most common biological entities on Earth. Experts estimate there are around 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 of them, and if they were all lined up they would stretch from one side of the galaxy to the other.

You can think of them as nature’s own nanotechnology: molecular machines with sizes on the nanometre scale, equipped to invade the cells of other organisms and hijack them to reproduce themselves. While the great majority are harmless to humans, some can make you sick and some can even be deadly.

Are viruses alive?

Viruses rely on the cells of other organisms to survive and reproduce, because they can’t capture or store energy themselves. In other words they cannot function outside a host organism, which is why they are often regarded as non-living.

Outside a cell, a virus it wraps itself up into an independent particle called a virion. The virion can “survive” in the environment for a certain period of time, which means it remains structurally intact and is capable of infecting a suitable organism if one comes into contact.

When a virion attaches to a suitable host cell – this depends on the protein molecules on the surfaces of the virion and the cell – it is able to penetrate the cell. Once inside, the virus “hacks” the cell to produce more virions. The virions make their way out of the cell, usually destroying it in the process, and then head off to infect more cells.

Does this “life cycle” make viruses alive? It’s a philosophical question, but we can agree that either way they can have a huge impact on living things.

What are viruses made of?

At the core of a virus particle is the genome, the long molecule made of DNA or RNA that contains the genetic instructions for reproducing the virus. This is wrapped up in a coat made of protein molecules called a capsid, which protects the genetic material.

Some viruses also have an outer envelope made of lipids, which are fatty organic molecules. The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 is one of these these “enveloped” viruses. Soap can dissolve this fatty envelope, leading to the destruction of the whole virus particle. That’s one reason washing your hands with soap is so effective!

What do viruses attack?

Viruses are like predators with a specific prey they can recognise and attack. Viruses that do not recognise our cells will be harmless, and some others will infect us but will have no consequences for our health.

Many animal and plant species have their own viruses. Cats have the feline immunodeficiency virus or FIV, a cat version of HIV, which causes AIDS in humans. Bats host many different kinds of coronavirus, one of which is believed to be the source of the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Bacteria also have unique viruses called bacteriophages, which in some cases can be used to fight bacterial infections.

Viruses can mutate and combine with one another. Sometimes, as in the case of COVID-19, that means they can switch species.

Why are some viruses so deadly?

The most important ones to humans are the ones that infect us. Some families of viruses, such as herpes viruses, can stay dormant in the body for long periods of time without causing negative effects.

How much harm a virus or other pathogen can do is often described as its virulence. This depends not only on how much harm it does to an infected person, but also on how well the virus can avoid the body’s defences, replicate itself and spread to other carriers.

In evolutionary terms, there is often a trade-off for a virus between replicating and doing harm to the host. A virus that replicates like crazy and kills its host very quickly may not have an opportunity to spread to a new host. On the other hand, a virus that replicates slowly and causes little harm may have plenty of time to spread.

How do viruses spread?

Once a person is infected with a virus, their body becomes a reservoir of virus particles which can be released in bodily fluids – such as by coughing and sneezing – or by shedding skin or in some cases even touching surfaces.

The virus particles may then either end up on a new potential host or an inanimate object. These contaminated objects are known as fomites, and can play an important role in the spread of disease.

What is a coronavirus?

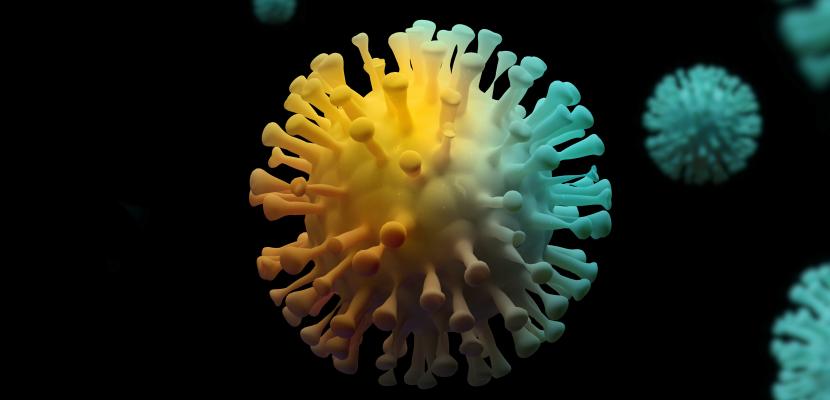

The coronavirus COVID-19 is a member of the virus family coronaviridae, or coronaviruses. The name comes from the appearance of the virus particles under a microscope: tiny protein protrusions on their surfaces mean they appear surrounded by a halo-like corona.

Other coronaviruses were responsible for deadly outbreaks of Serious Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in China in 2003 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) from 2012. These viruses mutate relatively often in ways that allow them to be transmitted to humans.