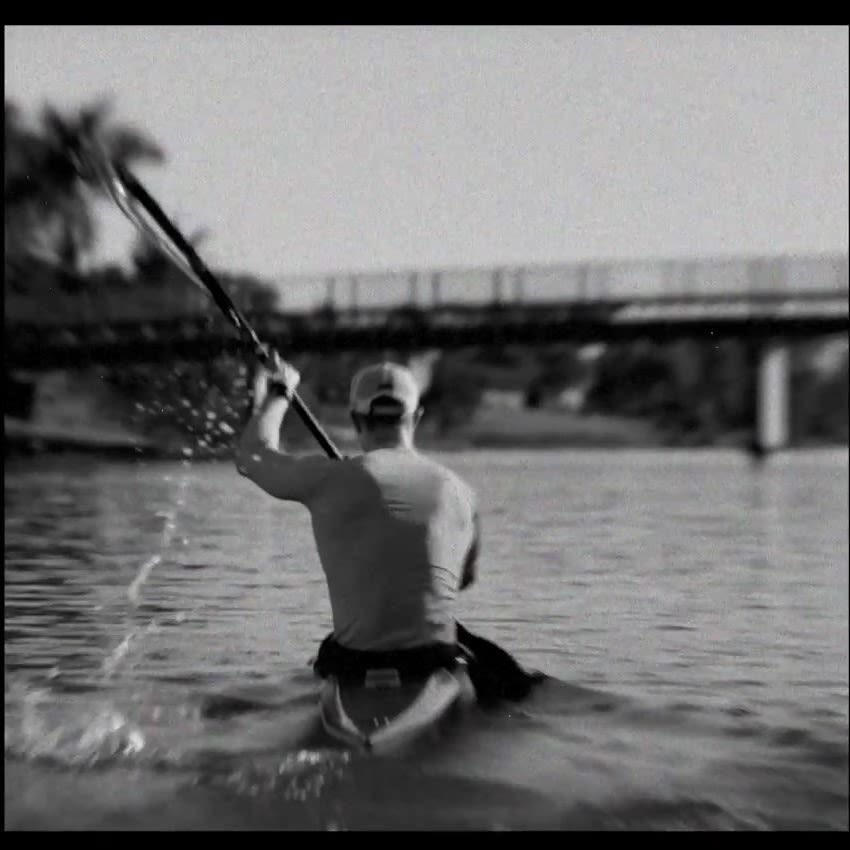

Actuarial Science student Pierre van der Westhuyzen and his older brother Jean (Class of 2018) were selected in the Australian Sprint Canoe team at the 2024 Paris Olympics. Bond's Dr Mike Todorovic and Dr Greg Cox have used them as a case study to help us understand the anatomy of an Olympian.

Pierre and Jean are fast, strong, and disciplined. Some may speculate that their genetics have helped the brothers secure their spot at the Paris Olympics. But the Bondies have dedicated thousands of hours to planning, training and eating in pursuit of their dreams. So just how much of their success comes down to nature and how much is nurture? We've drawn on the experts to explain the make-up of elite athletes, and whether anyone could become an Olympian.

What sets an Olympian apart from a person of average fitness?

Olympians and elite athletes have differences in their nervous system, their cardiovascular system, respiratory system and muscular system. This is due to adaptations their bodies have made during training.

“Exercise can be beneficial to our health but it’s also a stressor. Your body responds to that stress so it can handle it better the next time you perform that exercise.”

Changes in an athlete’s body can include the heart growing bigger and stronger so it’s more efficient at pumping blood. Dr Todorovic says, in some instances, an Olympians’ heart will be 50 per cent thicker than average, allowing it to pump more blood with fewer contractions.

Other changes in the body include the blood vessels growing more responsive and dynamic to blood pressure changes.

Muscles will respond to lifting and pushing weights by growing in size as they repair, in order to lift the weights more easily in the future.

“Each individual will adapt differently depending on the training stimulus,” Dr Todorovic says.

What Olympian qualities do Pierre and Jean have?

Sprint kayakers, including Pierre and Jean, typically possess a lean body composition, a proportionally large upper body (big arms and chest), and narrow hips. These structural attributes are essential for their sport.

“Obviously being brothers, Pierre and Jean share 50 per cent of their DNA so they're going to share significant similarities in regards to their body composition and proportions,” Dr Todorovic explains. The brothers also have an exceptionally high absolute aerobic power, particularly in their arms. Studies indicate that sprint kayakers exhibit remarkable muscular strength, anaerobic capacity, and endurance in arm exercises, such as shoulder extensions.

“Impressively, the maximal force they can produce during these exercises rivals that of bodybuilders, but with much less fatigue.”

How big of a role do genetics play?

Genetics determine certain physical attributes that can influence an individual's suitability for specific sports. It's uncommon to see a 5-foot-tall basketball player or a 7-foot-tall gymnast, as genetics strongly control traits like height, limb length, and body composition. Retired American basketball player, Tyrone “Muggsy” Bogues, is a notable exception at 5-feet, 3-inches tall.

“Studies have identified around 200 common genetic variations, known as polymorphisms, associated with physical performance,” Dr Todorovic says. “These genetic factors can affect muscle composition, aerobic capacity, and other attributes critical for athletic success.

“However, genetics are not the sole determinant of athletic performance. Environmental factors such as training, nutrition, and sleep play an enormous role in the development and success of an athlete.”

While genetics provide a foundation, it is the combination of genetic potential and environmental influences that ultimately shapes athletic achievement.

How does diet play into performance?

Getting the right nutrients through diet can push an athlete to their personal best. Bond University Associate Professor and sports dietitian Dr Greg Cox says it’s crucial for athletes to be strategic with their daily food and fluid intake, to support daily training performance, recovery and well-being. Training, such as that undertaken for sprint kayaking, improves the body’s ability to transport, store and subsequently use fuel, namely fat and carbohydrate, in the muscle.

“During high intensity exercise, carbohydrate is the most important fuel to the active muscle,” says Dr Cox. “The right combinations of nutrients, well-timed around training, will optimise an athlete’s response and ultimately support performance at major competitions — such as the Olympics.”

Dr Cox says elite athletes need to plan and have strategies in place to respond to travel and changes in daily training. He was in Paris supporting the Australian Dolphins swimming team ahead of the games.

“The Olympics is like no other sporting event as athletes are faced with navigating the Olympic Dining Hall — the largest food truck in the world,” he says. “Australian Olympians are well supported during their final steps ahead of Olympic competition by an army of accredited sports dietitians.”

Australian athletes competing at the Olympics have access to a handful of tailor-made nutrition supports including a personalised “performance pantry”, recovery eskies to support training and competition venues, familiar Aussie breakfast options, and even an on-site café supported by Australian baristas.

Do Olympians have different brain anatomy?

Yes, the brain — and nervous system more broadly — is wired differently in elite athletes, from the way they receive information to the way they interpret and respond. Dr Todorovic says the brains of athletes are different to non-athletes, both in structure and function.

"Studies have shown the grey matter and the white matter within the brains of athletes are different compared to non-athletes, especially in areas associated with sporting performance," he says.

In athletes, the areas associated with detecting information, which we call sensory processing, and areas associated with physical activity, which we call motor control, have stronger and more efficient connections. "That means athletes have better and faster reflexes," Dr Todorovic says.

Athletes also have superior cognitive performance than most non-athletes, particularly attention allocation and cognitive flexibility.

Athletes also have superior cognitive performance than most non-athletes, particularly attention allocation and cognitive flexibility. "In a sporting environment, they can focus better on a moving ball, target or opponent."

In Jean and Pierre's case, they can focus on their performance, while ignoring the action happening around them.

In terms of cognitive flexibility, athletes have improved ability to change what they're thinking about in the moment as well as adapt their behaviours in response to changing environments or goals.

"In the sporting arena, athletes are able to respond quickly to make the best decision possible when something unexpected happens during a game or a race," says Dr Todorovic.

Could any person of average health and fitness develop all the qualities required to be an Olympian?

It’s possible, but not everyone is born with the genetics that would allow them to reach an Olympic level.

“In short, for a person of average health and fitness to become an Olympian, it would require significant lifestyle changes and an extraordinary level of dedication,” Dr Todorovic says. “While not everyone has the genetic makeup that may tweak one’s physical performance to obtain elite status, many can achieve high levels of athletic performance through persistent effort and optimal training.”

Dr Cox says well-chosen and timed food and fluid intake will support the body’s response to daily training as well as maintain health and well-being.

“Our focus of how nutrition best supports elite athletes has changed considerably in the past 10 years,” he says. “Staying healthy, while managing the rigours of strenuous daily training forms the cornerstone of an athlete’s diet.”

How long would it take an average person to become Olympian fit?

There are too many variables to give a definitive answer, but Dr Todorovic can give an idea of the weekly commitment.

“Let’s put the training of a world-class track runner (5,000 metres and 10,000m) into perspective. On average, each week, they would perform 11-14 training sessions and run between 130-190 kilometres,” he says.

This doesn’t include their nutritional requirements, sleep and — let’s not forget — work.”

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond