Australians’ love of the beach is marred by a common fear — sharks. Statistics show unprovoked shark bites are increasing around the world, including on our shores, so is the concern founded? And, in examining our fear, do we need to consider our own role in the rise?

Associate Professor of Environmental Science Dr Daryl McPhee explains what’s behind the increasing incidence of shark bites, how humans have impacted the trend, and personal accountability when entering the ocean.

How have trends in shark bites changed over time?

Shark-human interactions have increased globally, with 69 confirmed unprovoked bites reported in 2023. Dr McPhee says the species responsible for most are the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier), and bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas).

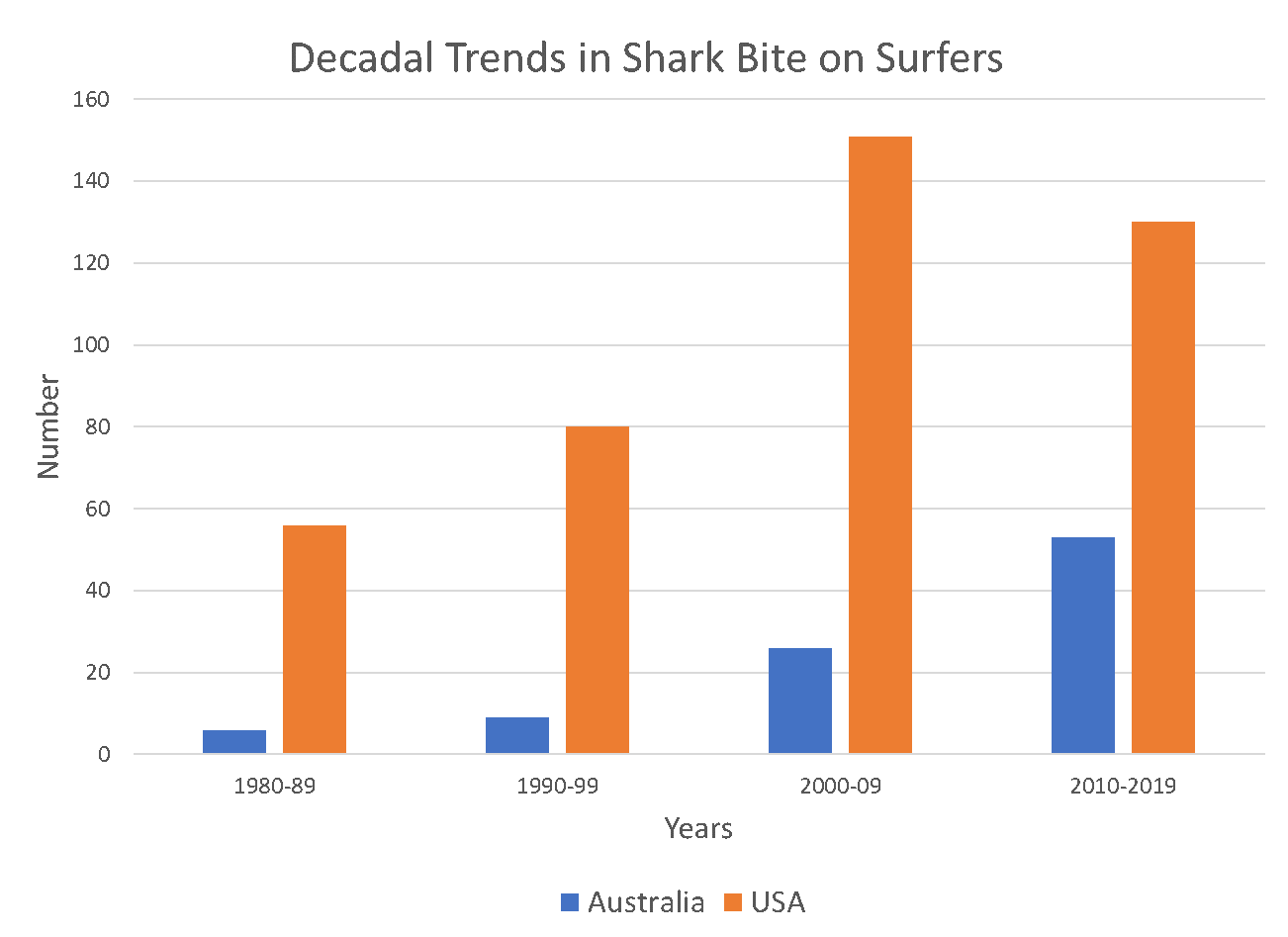

Most shark bites occur in the United States, followed by Australia. Bites on surfers have increased significantly in both countries in recent decades, as bigger populations hit the beaches. In New South Wales, shark bites shifted from being predominantly on swimmers in 1900 to surfers by the 1980s.

Is the rise in shark bites cause for concern?

While incidences of bites have risen over time, the risk is still very low. “You are about 20 times more likely to drown at a surfing beach than be killed by a shark. And, if you’re a surfer, you’ve got more chance of sustaining a physical surfing injury than any injury from a shark,” Dr McPhee says.

He goes on to explain that the low risk of being killed by a shark is disproportionate to the amount of fear people hold, likely because of the portrayal of sharks in the media. In reality, sharks come in all sorts of weird and wonderful forms across about 370 species, from the gentle giant 12m whale shark to a 20cm shark that rarely sees the surface. Only a few of these species have been reported to bite humans, and we are not part of their natural diet.

Why are shark bites happening more often?

There’s no single factor. Dr McPhee says while an increased number of people participating in water activities is an obvious contributing factor, it’s more complicated than that correlation. Environmental factors, distribution of prey, and changes to habitat are other potential influences.

“One contributing factor, certainly on the Australian east coast, can be an increased number of whales because large white sharks eat whales,” he says. “On the American east coast around Massachusetts, there has been the recovery of a grey seal population and the white sharks have followed. But there’s never one single reason for an increase in shark bites; there's always a range of reasons.”

Dr McPhee gave another example where a large cluster of shark bites in Recife in Brazil was believed to be a result of the changed environment. “There was a large port development which displaced sharks onto a beach where bites then occurred,” he says.

It’s not uncommon for more than one bite to occur in a location in a short period of time. “We've seen it in other places in northern New South Wales, Western Australia, South Australia, and South Africa. When the conditions are right, when sharks are present and feeding adjacent to areas where people are using the water, that's when you might get a clusters of bites,” Dr McPhee says.

He says researchers are yet to have solid information on population trends for white, tiger and bulls sharks.

Why do sharks have a bad reputation?

Shark bites are uncommon but can have a catastrophic impact on the victim. “A shark bite is a low probability, high consequence phenomenon,” Dr McPhee says. Australia’s strong beach culture sees the impact felt widely across communities. In combination with the rarity, human interest, and controversy around mitigation, shark bites are highly newsworthy. This plays into the fear attached to a shark bite.

“Widespread reporting increases people's belief that the probability of a shark bite is higher than it actually is,” Dr McPhee says. Sharks are most often portrayed in the media and movies in a “generic and homogenous” way. Think human-eating and aggressive, like 1970s horror film Jaws. This is despite the fact that most rarely encounter humans, and feed on small fish.

Dr McPhee says the tendency to gets clusters of bites also moves the discourse from an accident to a trend, gaining momentum in the media, further instilling fear, and sparking emotional and reactionary political decisions.

Are shark nets effective?

Dr McPhee says it’s difficult to prove shark nets are certain to work because it’s impossible to carry out experiments in a practical or ethical way. “There's certainly correlative information in Queensland it has a positive effect on the community — it's an effective placebo,” he says.

While data indicates some shark nets and drumlines catch target sharks, potentially preventing incidents with humans, they also capture large amounts of non-target animals including turtles, stingrays, dolphins and whales. Catch records from New South Wales’ Shark Meshing program show 255 animals were entangled in nets from 1 September 2023 to 30 April 2024. Only 6 per cent were the target species of white, tiger and bull sharks. In Queensland, mitigation gear caught 1,096 animals in 2023, including 38 turtles, 11 humpback whales, 12 dolphins and more than 30 rays.

Dr McPhee says governments are heavily investing in alternative approaches, but there’s yet to be an efficient solution to replacing shark nets.

How can we keep ourselves safe?

While the odds of being bitten by a shark is less than one in a million, there are ways to reduce the risk. Swimmers and surfers should avoid entering the water if there are large schools of fish that could attract sharks, steer clear of murky water and river mouths after heavy rain, avoid the water in hours of low light and at night when sharks are most active, and swim at patrolled beaches where lifesavers or lifeguards survey the water.

Ultimately, Dr McPhee says safety comes down to people taking personal responsibility and accepting the risks of entering the ocean.

“We don't expect state governments to make mountain bike tracks 100 per cent safe, but we seem to put the onus back on them to make the ocean 100 per cent safe, 100 per cent of the time.”

“We don't expect state governments to make mountain bike tracks 100 per cent safe, but we seem to put the onus back on them to make the ocean 100 per cent safe, 100 per cent of the time.”

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond