Calculated move

Professor Terry O'Neill retires as Executive Dean of the Bond Business School

Calculated move

Professor Terry O'Neill retires as Executive Dean of the Bond Business School

By Ken Robinson

Born a 1 in 3,136 statistical anomaly, he has spent half a century making sense of complex data and teaching others the power of numbers.

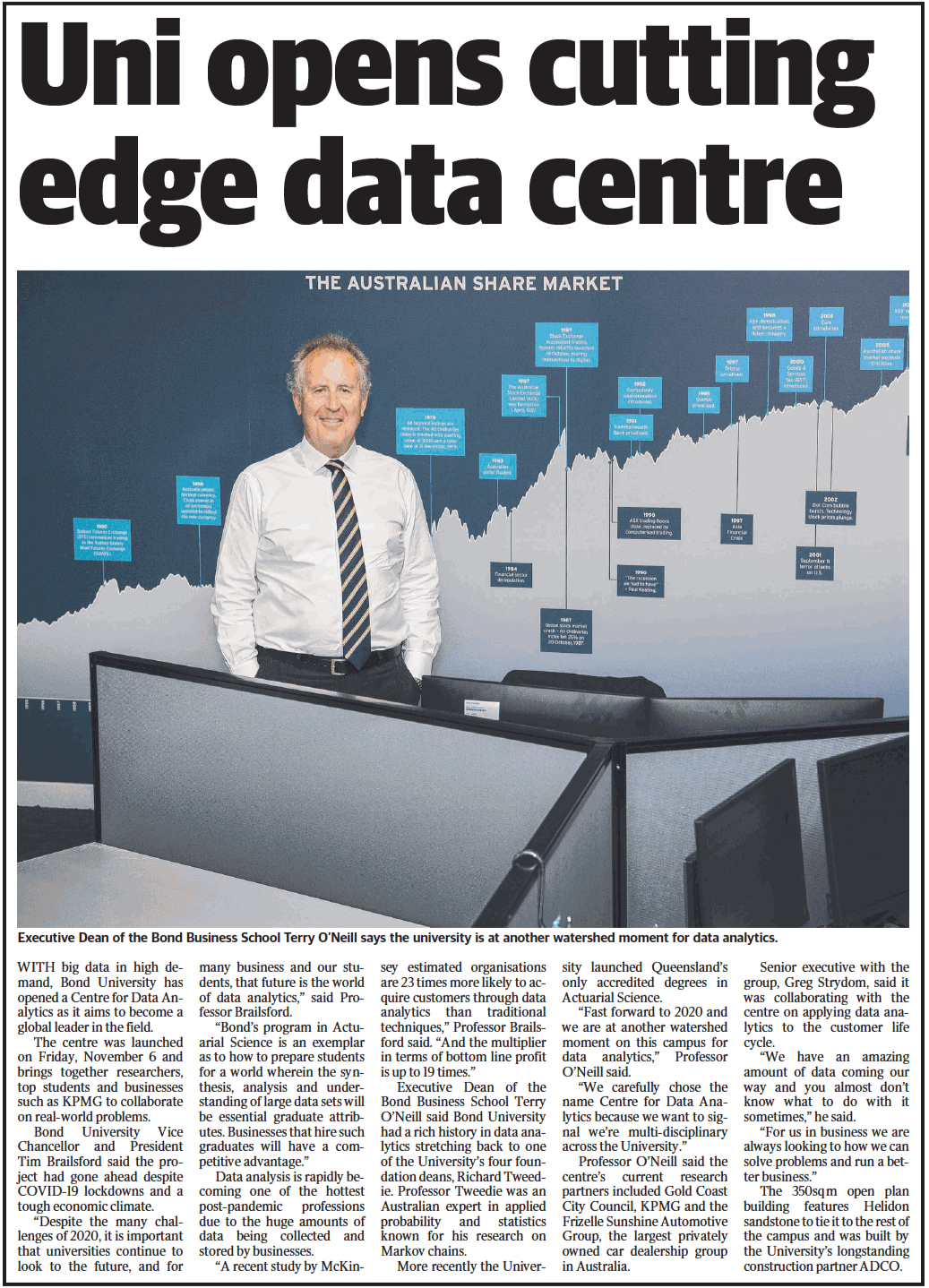

Leave it to a statistician to pinpoint the perfect moment to retire – and yes, equations are involved. Professor Terry O’Neill is leaving Bond University after a decade of service, most of it as the foundation Executive Dean of the Bond Business School and Director of the Centre for Data Analytics.

He has spent more than 50 years of his life immersed in calculations impenetrable to most people, yet they carry significant real-world consequences. Among his work: suggested intervals for breast cancer screening that shaped Australian medical guidelines, and how to extract useful insights from car crash data.

Both of those series of studies undoubtedly saved lives but it was a 2001 paper Estimating cohort health expectancies from cross-sectional surveys of disability that got him thinking about his own mortality.

“We were looking at the increase in life expectancy and wondered, how much of that extra time is enjoyable?” Prof O’Neill said. “The conclusion was that for most of those later years, you're going to be pretty miserable. It was not a very uplifting outcome but it's a realistic assessment of what happens.”

A 72-year-old man can only ski for so long, and this one is going to get his turns in on the slopes of Japan while he still can.

Terry O'Neill, second from right, hold his brother Gary, while his twin sister Sherry holds Gary's twin brother Barry.

Terry O'Neill, second from right, hold his brother Gary, while his twin sister Sherry holds Gary's twin brother Barry.

Born a mathematical rarity

Prof O’Neill was born in Adelaide among the eldest of two sets of twins – three boys and a girl. Statistically, the likelihood of a woman having twins twice is 1 in 3,136. Practically, it meant a mother with four children under the age of two and their father, a former railway fitter and turner who became a Holden executive, dealing with a headache.

“When my mother found out she was pregnant with her second set of twins she left a message for Dad at work,” Prof O’Neill said. “By the time she got home he was sitting at the kitchen table with his head in his hands saying, ‘What will we do?’ They owned a block of land and that night Dad started building a house on it. He would finish at Holden and work on the house at night under the streetlights.”

Prof O’Neill attended local primary and high schools and was quickly identified as academically gifted, marked down only for being a left-hander who smudged his work. Living in Hendon, not far from Adelaide’s beaches, he and his two younger brothers joined Grange Surf Life Saving Club, the dominant surf club in South Australia in the 1960s and 70s.

Terry O'Neill, centre, with his brothers and other members of the South Australian Surf Life Saving team.

Terry O'Neill, centre, with his brothers and other members of the South Australian Surf Life Saving team.

The strong swimmer made the state team twice while brothers Barry and Gary were, respectively, a champion ironman and a life member of the club. When it came time to consider university – not always a given, even for very bright students in the late 1960s – he prevaricated.

“I really liked maths and I kind of liked science,” Prof O’Neill said. “I thought about medicine but decided to go for a science degree at Adelaide University. As I worked my way through the degree I began to focus on statistics which was a real revelation to me. I thought it was fascinating to see what people could do with data.”

While at university he ran into a girl he had known at high school. The future Professor Helen O’Neill would become his life and research partner.

Bound for Stanford

After graduating with honours and prizes, including for the top science student, there were several scholarships for postgraduate study on offer. A Commonwealth Scholarship could take him to the UK but the downside was you didn’t get to pick the university.

“I had my heart set on Oxford or Cambridge but they said I was going to Sheffield University because Joe Gani, who was very influential in statistics and later ran the CSIRO Mathematics and Statistics Division, was there at the time. I wasn’t sure I wanted to go to Sheffield. I had also applied to one place in the US, and that was Stanford.”

Today Stanford is ranked among Oxford, Harvard and Princeton as one of the finest universities in the world. It was still quite prestigious in the early 1970s, but this was before it became an epicentre of the computer revolution and what would become known as Silicon Valley.

“It was very non-standard decision at the time,” Prof O’Neill said. “Helen had finished at Adelaide Uni and was planning to go to Berkeley while I was at Stanford, but we hadn’t studied our geography and they’re at different ends of San Francisco Bay, so that wasn’t very practical. She ended up working for Stanford University Medical Centre and began her lifetime interest in immunology there.”

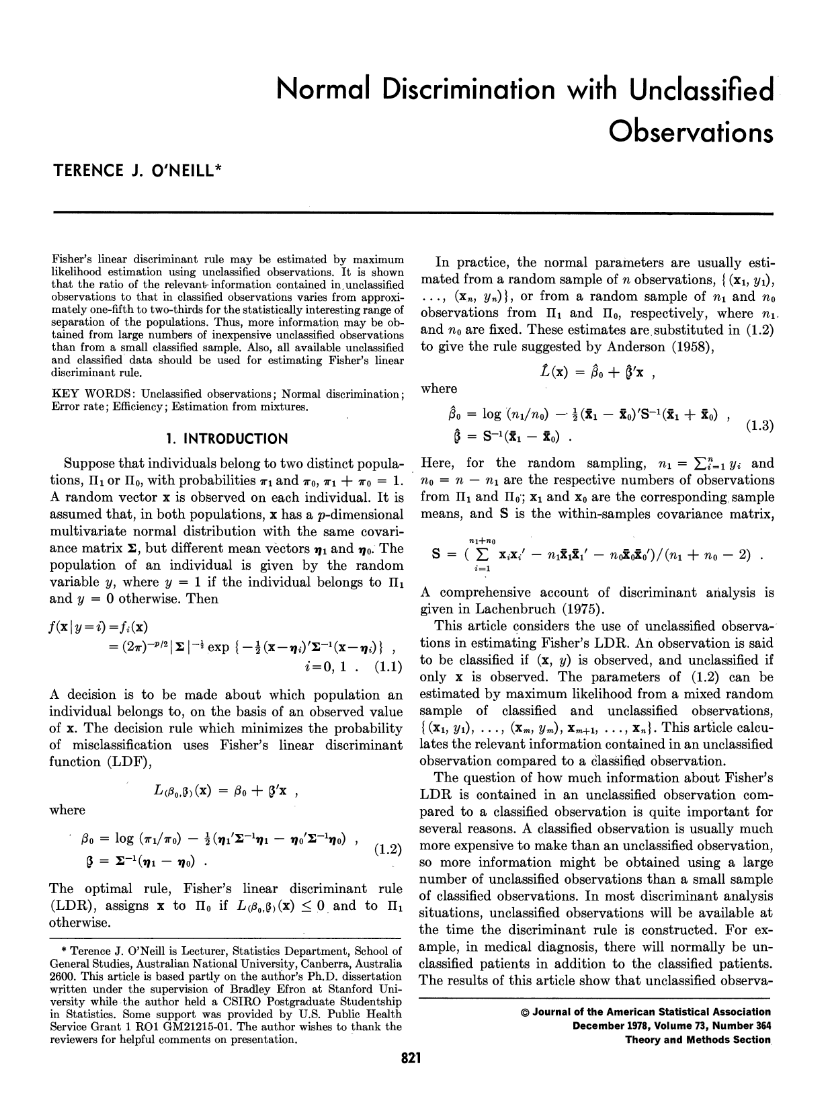

Prof O’Neill attended Stanford on a CSIRO postgraduate scholarship and with an exchange rate of about A$1.50 to the US dollar, he and Helen enjoyed a lifestyle better than most of his fellow PhD students. With Professor Brad Efron as his PhD supervisor (Efron is arguably the best-known statistician in the world), Prof O’Neill turned in his thesis in 1976 and the paper Normal Discrimination with Unclassified Observations was published in the Journal of the American Statistical Association. Then came the first of several difficult decisions as he returned to Stanford again and again during his career, including as a Fulbright Fellow. Would the young couple stay, or return to Australia?

“There are points in life, like finishing a PhD, where you think, am I in the right place or not?” Prof O’Neill said. “Palo Alto is an oasis and we had some very good job offers in the US but we hadn’t been home the entire time we were at Stanford, so it seemed like a good time to come back.”

Return to Australia

Prof O’Neill committed to academia fulltime, lecturing in statistics at the Australian National University and raising two sons with Helen. As he gained seniority, he became aware of a new university on the Gold Coast. Among his colleagues to make the move to Bond University was Professor Richard Tweedie who became Dean of the School of Information & Computing Sciences. The early 1990s were tumultuous times for Bond University as it bounced from one financial crisis to the next.

“Helen was actually interviewed for a job at Bond but by the time she landed back in Canberra they had phoned her to tell her the science faculty had just been dissolved,” he said.

Prof O’Neill became the inaugural Head of Department of Statistics & Econometrics at ANU in 1995. Not long after, a Brailsford, T.J. started popping up as a co-author on some of Prof O’Neill’s research papers. Nearly two decades later, Prof Tim Brailsford, by this time Vice Chancellor and President of Bond University, asked his former colleague if he would take on a special project.

“I was sitting in Canberra where the cold of winter was starting to wear me down, and I was not a particularly young man anymore,” he said. “Both our sons had left home and Canberra, and the VC said, ‘How would you feel about starting up the first actuarial science program in Queensland?’ We set it up in record time and were fully accredited within three years.”

It was a prescient move. Historically, actuaries were mainly confined to the insurance and finance industries. However, the masses of data now being collected by nearly every business – and the opportunity to interpret and monetise it – has led actuaries to expand into a broad spectrum of industries.

Prof O’Neill was soon confirmed as Interim Dean of the Bond Business School, then foundation Executive Dean. Keen to build on his strong research pedigree, he launched what would become the Centre for Data Analytics at Bond University. The centre is now a leading research hub in the field, collaborating with governments, private enterprise and not-for-profit organisations.

Looking ahead

With about 100 journal publications to his name, Prof O’Neill said the aforementioned analyses of breast cancer and car accident data, along with his PhD on classification theory, are among his proudest work.

“The PhD was fairly revolutionary at the time and we’re still playing in that space today,” he said. “I also did some nice research with Helen over the years. I find her work (in genetics) really interesting.”

Prof O’Neill said as computing power and AI automate many tasks previously performed by humans, interpersonal skills will become more important.

“The students are front and centre of everything we do at Bond, and I hope we continue to innovate, introduce new technologies, and enhance the students’ experience to better prepare them for the evolving business landscape,” he said. “It's evident that AI will play an increasingly significant role, but deals will still involve face-to-face negotiation. Skills like communication, strategy, and planning are becoming more crucial than ever in the professional world.”

Prof O’Neill described his career as a study in contrast.

Adelaide University.

Adelaide University.

Stanford University.

Stanford University.

The Australian National University.

The Australian National University.

Bond University.

Bond University.

“I started at Adelaide University, a very good public university, then switched to Stanford University, a really, really good private university,” he said. “Then I went to Australian National University, probably the most heavily government-supported university in Australia. Then came Bond, the first and best private university in Australia. What I like about Bond is the responsibility to provide for ourselves. There is no mindset that government should be doing more for us. The staff accept that our destiny is in our own hands and we all have a responsibility to provide for our own existence.”

Prof O’Neill said he and Helen – the other Professor O’Neill recently announced her decision to step down as the Director of the Clem Jones Centre for Regenerative Medicine at Bond University – were looking forward to escaping the “tyranny of the diary” and seeing more of Queensland.

“When we first moved to the Gold Coast we gravitated to Broadbeach and we've loved living there ever since,” he said. “Nearly all of our time in Queensland has been spent at Broadbeach or Bond, so one of the things we've got to do in retirement is take time to look around a little more. We have one son and his partner in Sydney, another son and his family settled in Hong Kong with four grandchildren, so I imagine we'll spend a fair bit of time there. I like skiing but that begs the calculation of, how many more good years do I have left?”

In recognition of his long and distinguished career, Bond University bestowed the title of Professor Emeritus upon Prof O'Neill. It is an honour given out less than 20 times in the University's history.

Professors Terry and Helen O'Neill.

Professors Terry and Helen O'Neill.

Original thinking direct to your inbox

Stories from Bond